Feed aggregator

Employer assessment fees are not an adequate solution to low wages and large safety net cuts

Too many U.S. employers are breaking the social contract by paying unfairly and inefficiently low wages. These low wages are one reason why even people who work regularly throughout the year can qualify for income assistance programs like Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Further, the Republican-led One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) that passed last year will sharply cut Medicaid and SNAP over the next decade by well over $1 trillion combined.

The combination of these trends—low-road employers paying insufficient wages and big upcoming cuts to Medicaid and SNAP—has led to a flurry of policy proposals at the state level to address them. One proposal—employer assessment fees (EAFs)—appears at first glance to address both problems by imposing a tax on firms that employ workers who receive Medicaid or SNAP, with the tax often calculated as the number of workers receiving these benefits multiplied by the average cost of those benefits. But EAFs are not the optimal solution to either problem and might cause undesirable collateral damage.

Here’s why:

- Medicaid and SNAP do not make it easier for employers to offer lower wages. In fact, they likely raise the wages needed to attract workers—and that’s a good thing.

- This is not universal across all safety net and income support programs. Some of these, like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), do see some of their benefits likely bypass workers and captured by low-wage employers.

- If you make Medicaid-receiving workers more expensive to employ, then employers will try to employ fewer of them and/or lower their market wages. And if the tax is proportional to the average cost of benefits like Medicaid, this incentive is large.

- Employer assessments fees are generally a large tax imposed on a small base. But revenue is maximized when tax bases are broad.

- The targets of EAFs can be more effectively reached with other policies.

- Raising minimum wages and passing legislation to strengthen workers’ rights to unionize and bargain collectively are alternative policies for forcing employers to pay more.

- Broad-based taxes are alternative polices for raising revenue.

- Higher corporate income taxes or employer-side payroll taxes would be more progressive alternatives for taxing employers.

- Another alternative would be to penalize firms that don’t offer employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) to workers. This is not a huge base, but it is by definition wider than those who receive Medicaid (which is just a subset of all workers not receiving ESI through the firm.)

Below, we expand on these points.

Medicaid and SNAP do not make it easier for employers to offer lower wagesA concern is often expressed that Medicaid and SNAP “subsidize” low-wage employers by making it easier for them to offer lower wages. Intuitively, thinking that Medicaid and SNAP subsidize low-wage employers actually gives these employers far too much credit for caring about the living standards of their workers. Higher pay is not given out of the goodness of employers’ hearts—it happens when policy or market conditions change. Medicaid and SNAP do not change labor market conditions in any way that lowers workers’ pay, and when these programs are cut in coming years, low-wage employers are not going to think “we need to raise our wages to help these employees who are seeing cuts to other income sources.” They will instead raise wages only if policy mandates they do or if market conditions change.

In reality, Medicaid and SNAP actually boost lower-wage workers’ meager leverage to demand higher pay by making periods of non-work less miserable. This slightly improved fallback position for low-wage workers keeps them from being forced as quickly by material deprivation into accepting any possible wage offer from employers. Policy changes that reduce how many workers receive Medicaid or SNAP will put further downward pressure on wages. We should support policies that expand the number of workers who have their wages supplemented by safety net programs, not policies that penalize and stigmatize using benefits.

This wage-boosting effect is not universal among all public income support programs. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), for example, pays more as workers supply more hours to the paid labor market. This boost to labor supply puts some downward pressure on market wages and can lead to some of the EITC benefits bypassing workers and being captured by employers (unless it is complemented by strong minimum wages.)

Making workers who receive safety net benefits more expensive will reduce demand for themIf you make workers who receive safety net benefits more expensive for employers to keep on payroll, then you increase the incentive for these employers to hire fewer of them or offer them lower wages.

Supporters of EAFs could argue this logic could be employed against any effort that made workers more expensive, like minimum wages. But minimum wages apply to all workers, and employers by definition cannot lower wages to absorb the higher costs minimum wages impose. Fully substituting away from workers whose pay has been lifted by minimum wages and toward other inputs essentially means employers would have to make costly investments in plant, capital, equipment, and processes.

Conversely, only a small fraction of workers receives safety net benefits. Absent binding minimum wages, employers can lower their market-based pay to recoup the EAFs (at least until they run into the relevant minimum wage in the labor market.) Trying to substitute away from workers who receive safety net benefits toward workers who are less likely to receive these benefits is more doable for employers than substituting away from all lower-wage labor.

These employer efforts to figure out who on their payroll is likely to trigger an EAF could lead to collateral damage. Workers from groups that are more likely to receive safety net benefits might be discriminated against across-the-board, regardless of whether or not they are actually enrolled in Medicaid or SNAP. Basically, EAFs mean that populations who are more likely to use benefits—like low-income single moms—would face even greater barriers in the labor market. Workers of color are also overrepresented among the families who use SNAP and Medicaid.

Further, the direct benefits of broad-based minimum wages to workers are large—all low-wage workers get a raise if their pay was lower than the new minimum. The direct benefits to any worker from an EAF is nonexistent—their pay does not rise, and they are not more likely to receive employer benefits.

The indirect benefits of EAFs are simply the revenue they raise, and if this revenue can be raised in less costly ways, then EAFs are not optimal.

EAFs are a large tax on a small baseWorkers who receive Medicaid benefits constitute roughly 10% of the overall workforce (and their share of total hours is significantly less than this). This is a relatively small base for a tax. But the size of proposed EAFs is often quite large, sometimes as large as the average Medicaid benefit. This benefit can reach more than $9,000 annually in many states. For a full-time, year-round worker making $15 an hour, this constitutes a tax on employers equivalent to 30% of that worker’s entire earnings.

Large taxes on small bases often lead to behavioral responses that erode the revenue gained from the tax. The large value of the tax incentivizes this avoidance behavior, and the small base allows substitution away from workers who trigger the tax. This means that EAFs would raise—at best—a highly uncertain amount of revenue and could well end up raising small amounts.

Sometimes, behavioral responses to taxes that reduce the revenue they raise are socially useful. For example, when cigarette taxes lead to reduced smoking or even when workers facing higher taxes are able to voluntarily substitute more leisure for work. But the behavioral response to EAFs that lowers the revenue gained from them also directly inflicts harm on low-wage workers.

There are better alternatives for the policy goals of EAFsThe recent pushes to use EAFs come from very good impulses: the desire to force employers to pay more and stop defecting on the social contract, and the desire to raise revenue so that states can buffer their residents from the terrible coming effects of the OBBB.

But there are better alternatives to achieve these goals. To raise wages, higher minimum wages are an obvious first step. A second step is policy changes that better enable willing workers to form unions and bargain collectively, even in the face of steep employer resistance. Policymaker inaction has largely destroyed the fundamental right of association in much of the U.S. labor market. Reversing this would, in the long run, solve many of the problems of employer behavior that EAFs are trying to target.

There are also better sources to raise reliable revenue to buffer residents from the OBBB’s steep cuts. If the desired target for these revenue increases is employers, higher corporate income taxes or higher employer-side payroll taxes (for all workers) could be used. Another revenue source specifically targeted at low-road employers could be increasing penalties for firms based on the number of their employees who are not covered by employer-sponsored health insurance through the workplace. This is not a huge tax base, but it is by definition larger than just employers with workers receiving Medicaid, as it would also include workers with no coverage at all. Further, this tax would incentivize the provision of ESI to more workers, a good thing in itself.

You can’t starve the public sector to excellence

Most people understand a basic truth: you get what you pay for. Skip maintenance on your roof, and you shouldn’t be surprised when leaks appear.

The same is true of government. If we want a high-functioning public sector—and we should—there is no shortcut. It requires sustained investment in the people and capacity that make government work. Starve it of resources, and its performance will inevitably suffer.

In a recent New York Times essay, academics Nicholas Bagley and Robert Gordon argue otherwise. In their telling, government underperforms because public-sector unions have too much power, driving up costs and resisting efficiencies. Their solution is simple: rein in unions and invest less—largely by cutting pay for public-sector workers. It’s a tidy story that promises an easy fix.

It is also economically incoherent.

The central constraint on public-sector performance is not the power of unions—it is chronic underinvestment. For decades, policymakers have allowed public-sector pay and prestige to fall behind comparable private-sector jobs and have outsourced key functions that should have been performed by skilled civil servants, not profit-maximizing private contractors that are the real source of excess costs for state and local governments. The predictable results have been staffing shortages, uneven service quality, and degraded state capacity—not because we are paying too much, but because we have been trying to get government on the cheap.

Start with the most basic implicit claim Bagley and Gordon return to again and again: that public-sector unions have extracted excessive compensation and resisted efficiencies at every turn. If that were true, we would expect to see the total compensation of public-sector workers rising as a share of the overall economy. In fact, the opposite has happened—the combined compensation of public employees has shrunk noticeably as a share of national income for the last quarter century.

To be sure, policymakers should always aim to deliver value for taxpayers. And—just as in the private sector—there are surely instances where some public employee’s pay is out of line or workers resist useful improvements. But if overpayment for services delivered inefficiently was a general feature of the public sector, their aggregate compensation wouldn’t be shrinking sharply over time.

Bagley and Gordon support their claims with a shotgun blast of anecdotes about public-sector unions able to muscle excess pay out of colluding Democratic politicians that are almost laughably context-free. L.A. Mayor Karen Bass gave larger-than-normal raises to public-sector employees in 2024? I’d hope so—prices had risen 23% in the previous five years (this inflation had made some news) and private-sector pay for non-supervisory employees was up 28% over that time. The suggestion by Bagley and Gordon that these raises were untoward only makes sense if you actively want the desirability of public employment to crater relative to the rest of the economy.

Bagley and Gordon also note darkly that “more than half” of local government expenditures are paid to employees. So what? Local government spending is not like federal government spending where the overwhelming majority of it is simple transfer payments—sending checks to people (Social Security) and medical providers (Medicare and Medicaid). Local governments must directly deliver public goods and services, like public education. That’s going to be done by people who need to be paid. The private sector, too, devotes the majority of its spending to labor (in the corporate sector, labor’s share is well over 70%.)

Even the data they cite for this irrelevant point show that compensation—including the benefits that Bagley and Gordon decry—in state and local jobs is lower than for similar workers in the private sector. That gap matters. Public-sector employers must compete in the same labor markets as everyone else, and low relative pay for skilled workers in the public sector compromises the ability of public-sector employers to attract and retain highly effective workers.

This ignorance of how labor markets in the private and public sectors interact is the root of many of Bagley and Gordon’s economic misunderstandings.

Consider their discussion of education spending, where they note that California spends more per pupil than Mississippi. California does spend more per pupil in nominal dollars, but prices in California are far higher than in Mississippi. Even more importantly, private-sector salaries for college-educated professionals in California are much higher than in Mississippi—and those are the jobs that set the outside options that talented college graduates weigh when deciding whether to enter and remain in teaching. Put another way, it is competition from the private sector that determines how high pay must be to attract and retain high-quality teachers. Education researchers know this, and that’s why the generally accepted way to assess the sufficiency of education spending is not nominal dollars spent per pupil, but per pupil spending scaled to per capita GDP in a state. In forthcoming work we show that on this measure, California ranks 36th in the nation—lower than Mississippi.

This also shows why the Bagley and Gordon claim that “…blue states and cities often also pay state and local government workers more than similar jobs pay in red jurisdictions, even after adjusting for the cost of living” misses the point so spectacularly. State and local governments are embedded in their local economies and public-sector pay has to rise in line with private-sector pay in the economy around them, or the quality and quantity of available public employees will suffer.

The big problem over recent decades is that public-sector pay has not kept pace with the surrounding economy, which has made it harder to recruit and retain qualified workers. Teacher shortages, for instance, stem directly from the huge gap that has emerged in recent decades between what public school teachers earn and what comparable private sector workers earn, even in the highest-spending states. How would making these jobs lower-paying and lower-prestige add excellent new teachers and improve educational outcomes?

Another common complaint about the public sector is that it slows infrastructure projects. The public is often invited to imagine huge teams of paper-pushing bureaucrats gleefully stamping “no” on planning documents. But the clearest finding in empirical research about the drivers of higher-cost infrastructure is that costs have risen fastest where states reduced the number of transportation department employees. Fewer public-sector workers means that more of the planning work has been outsourced to more expensive private consultants.

Bagley and Gordon claim that when policymakers bargain with public-sector unions, there is no constraint on their incentives to grant union demands in exchange for electoral support. In reality, there is a crushing countervailing constraint—the overwhelming perception that voters are rabidly anti-tax. This results in a deep reluctance by policymakers to call for the level of revenue needed for public sector excellence. It is a far bigger structural problem today than any supposed excess power of public-sector unions.

Public-sector workers don’t just bear the brunt of underinvestment, they are also one of the few consistent voices arguing for robust financing of state and local governments, bargaining directly for the public good. They advocate for libraries to remain open in rural communities so that everybody has at least some access to the internet, for higher levels of K–12 education spending, and for proper training for EMTs and other first responders to ensure public safety.

Despite these efforts, public sector financing has been throttled in recent decades, and the results have been a predictable degradation of services. Even worse is coming, as the Republican tax and spending megabill will impose crushing cuts to safety net programs that states administer and jointly fund.

For decades we have been relying on the admirable intrinsic motivation of public employees to shield us from some of the damage of underinvestment—nurses, first-responders, and teachers going above and beyond the strict demands of their jobs to provide services they feel called to perform. But we’ve already asked too much while paying too little. If we want a truly excellent public sector—and we should—we need to pay for it.

Estimating the Budgetary Cost of U.S. Commitments to the International Monetary Fund: Working Paper 2026-02

How Budgetary and Economic Outcomes Might Differ From CBO's February 2026 Projections

Jack Smith's Secret Orders Targeting Patel And Wiles Should Alarm Us All

Former Special Counsel Jack Smith has long operated under Oscar Wilde’s rule that “the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.”

Over the last few months, the public has learned of a wide array of secret orders targeting members of Congress, Trump allies, and others.

Now, the Administration has learned that FBI Director Kash Patel and White House Susie Wiles were also targeted by Smith in 2022 and 2023 when they were private citizens.

Smith was a controversial choice as Special Counsel because of his history of excessive legal arguments and tactics, including his unanimous loss before the Supreme Court in tossing out the conviction of former Virginia Governor Robert McDonnell.

His tendency to stretch the law to the breaking point also did not play well with juries in high-profile cases, as in his case against John Edwards, which ended in acquittal.

Despite such criticisms, Smith immediately returned to his past pattern of tossing aside any restraint or caution. Even Democrats this year expressed objections to his targeting of Republican members of Congress, including former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy.

Smith told carriers not to tell members of Congress that their calls were being seized. Not only did such records reveal potentially confidential sources, ranging from journalists to whistleblowers, but Smith’s gag order prevented Congress from responding to check the abusive demand.

Now, the Administration is alleging that Smith and the prior Administration effectively buried the targeting of Patel and Wiles. It took a year into the new Administration for these orders to be uncovered.

The early accounts of the orders contained equally disturbed elements. Reuters reported that “in 2023, the FBI recorded a phone call between Wiles and her attorney, according to two FBI officials. Wiles’ attorney was aware that the call was being recorded, and consented to it, but Susie Wiles was not.”

It is astonishing to hear of a lawyer agreeing to the FBI recording of an attorney-client meeting as a general matter.

However, to do so without informing your counsel would be a breathtaking invasion of such protected communications.

There is much we still do not know.

On its face, these orders appear consistent with the earlier abusive demands. Smith had virtually no basis for targeting Republican members and Trump allies. It was a fishing expedition in which Smith simply compiled lists of every well-known ally of President Trump.

There are also concerns over the response to this controversy. There are reports of 10 FBI employees being fired. Agents often carry out the orders of superiors in such investigations. The Administration should assure the public that these agents were afforded due process before being ousted due to their work on orders.

The recently disclosed files from these investigations are an indictment of Smith himself. He was given a historic mandate to investigate a former president. Rather than exercise a modicum of restraint to show the public that this was not a partisan effort, Smith yielded to his worst temptations in targeting a long list of Republicans.

In his prior testimony, Smith offered little to justify these orders beyond a shrug that such secret orders routinely occur. However, he was targeting a “who’s who” listing of top political opponents to President Biden and the Democrats.

To make matters worse, Smith struggled to release damaging information (and even schedule a trial) on the very eve of the 2024 presidential election. Every action that Smith took only magnified his agenda to influence the election. He became a prosecutor consumed by his antagonism toward Trump and his unchecked power.

Nothing was sacred for Smith. His demands in the investigation from the courts included a wholesale attack on free speech values.

Ultimately, these files are not only an indictment of Jack Smith but also of former Attorney General Merrick Garland, who failed to exercise his authority to oversee Smith and protect core constitutional values.

It is essential that Congress and the Administration fully investigate Smith’s surveillance demands. Smith has long demanded accountability for others while evading such accountability for his own actions.

If past orders are any indication, the Patel and Wiles orders were likely based on sweeping generalities and demands for absolute secrecy. That is the signature of Jack Smith. Indeed, Smith appears to have replicated his increasingly infamous record with the collapse of two high-profile cases and lingering questions over his judgment and actions.

He has again yielded to his temptations, and the public has paid the price.

Jonathan Turley is a law professor and the author of the New York Times bestselling “Rage and the Republic: The Unfinished Story of the American Revolution.”

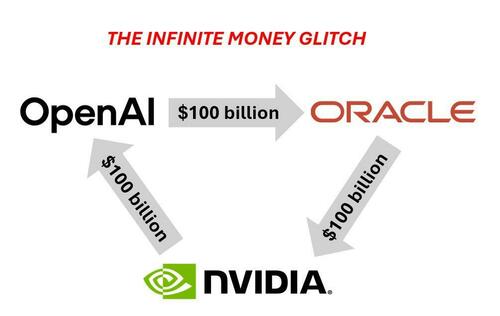

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 09:40OpenAI Secures Record $110 Billion Funding Round Backed By Amazon, Nvidia, & SoftBank

OpenAI has closed a new funding round that could total $110 billion, valuing the ChatGPT maker at $730 billion pre-money and potentially putting it on course for an IPO in the second half of the year, according to a new Financial Times report.

The three investors in the deal are Nvidia, Amazon, and SoftBank. People familiar with the deal say this opens the pathway to the public markets at the end of this year.

Breaking down funding numbers by strategic investors:

-

Amazon: $15 billion upfront, plus $35 billion later if OpenAI goes public or achieves AGI

-

Nvidia: $30 billion

-

SoftBank: $30 billion

-

Another $10 billion may come from sovereign wealth funds and other investors

The FT noted that the new funding round comes on top of the $40 billion already on OpenAI's balance sheet, giving the company more runway to rapidly expand and develop new models and AI infrastructure. OpenAI expects to remain unprofitable until 2030, when management forecasts it will turn free cash flow positive.

In a separate release, Amazon detailed its major multi-year partnership with OpenAI, centered on enterprise AI infrastructure, distribution, and custom model development.

Here are the highlights of the Amazon-OpenAI investment:

-

Amazon will invest $50 billion in OpenAI, with $15 billion upfront and another $35 billion later if certain conditions are met.

-

AWS and OpenAI will jointly build a "Stateful Runtime Environment" powered by OpenAI models and offered through Amazon Bedrock, aimed at helping customers run AI apps and agents with persistent context, memory, tool access, and compute.

-

AWS becomes the exclusive third-party cloud distribution provider for OpenAI Frontier, OpenAI's enterprise platform for building and managing teams of AI agents.

-

OpenAI will expand its AWS infrastructure commitment by $100 billion over 8 years, on top of an existing $38 billion agreement.

-

As part of that, OpenAI will use roughly 2 gigawatts of AWS Trainium capacity, spanning Trainium3 and future Trainium4 chips, to support Frontier, Stateful Runtime, and other advanced workloads.

-

OpenAI and Amazon will also develop custom OpenAI-based models for Amazon's customer-facing apps, giving Amazon teams another model option alongside its in-house Nova family.

"OpenAI and Amazon share a belief that AI should show up in ways that are practical and genuinely useful for people," OpenAI boss Sam Altman stated, adding, "Combining OpenAI's models with Amazon's infrastructure and global reach helps us put powerful AI into the hands of businesses and users at real scale."

Altman commented on today's announcement, saying, "As long as revenue keeps growing, the deals are not circular."

Well...

"As long as new investors keep coming, the Ponzi scheme won't unravel" - Bernie Madoff, maybe https://t.co/CZJRLTtAbk

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) February 27, 2026

Let's revisit our notes on the "circle jerk" AI vendor financing schemes as we've pointed out since last fall (read here & here).

Related:

The circle jerk keeps getting larger.

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 09:10US Begins Evacuating Some Embassy Staff In Israel 'While Flights Still Available'

"Persons may wish to consider leaving Israel while commercial flights are available," the US State Department announced Friday, signaling that US strikes on Iran could be imminent,.

It provided confirmation the US government has begun evacuating "non-emergency" personnel from the embassy in Israel and their family members, citing "safety risks" amid growing tensions with Iran.

via AFP

via AFP

The new urgent announcement also strongly suggests that whatever military action ensues, it will mostly likely involve a joint operation between the US and Israel. Some have warned that Washington is essentially about to go to war on behalf of what are fundamentally Israel's interests in the region.

People in Israel would further be at risk given the potential for Hezbollah to renew strikes on the country's north, and then there's the threat of Houthi attacks from the south - as happened in the last conflict in June and prior.

Fox correspondent Lucas Tomlinson has noted that the last time the embassy issued such an evacuation notice it occurred just eight days before Operation Midnight Hammer (the June strikes).

Another regional journalist, Idrees Ali, as observed: "Many of the things that happened before the United States and Israel struck Iran last year are happening now."

But this time around the military build-up by the United States is much, much bigger - and days ago hit levels not seen since the 2003 Bush-ordered invasion of Iraq.

On February 27, 2026, the Department of State authorized the departure of non-emergency U.S. government personnel and family members of U.S. government personnel from Mission Israel due to safety risks.

— U.S. Embassy Jerusalem (@usembassyjlm) February 27, 2026

In response to security incidents and without advance notice, the U.S.… pic.twitter.com/aWzX6Gk36x

Axios also confirms that while the US Embassy is still operating for now, "US ambassador Mike Huckabee wrote in a message to embassy staff that whoever wants to leave the country should do so Friday."

The State Dept. notice states further, "The ambassador, diplomats and U.S. personnel working on assistance to U.S. citizens, security, military, political and intelligence affairs will stay in the country."

Canada has also newly issued a warning Friday for its citizens to leave Iran and the Mideast region, warning about the near future availability of commercial travel.

Starting the countdown to yet another major US initiated war in the Middle East?...

Everything appears to be in place. Additional F-35s have been deployed, refueling tankers have reached their designated positions with more en route, and the USS Gerald R. Ford has arrived in Israeli waters. And no deal on the nuclear issue still. https://t.co/YP9t8oQ3AL

— Levent Kemal (@leventkemaI) February 27, 2026

This adds to a growing list of countries telling their population to avoid the region or leave, including: Finland, Serbia, Poland, Sweden, India, Greek Cyprus, Singapore, Germany, Brazil, and others. China has also told its citizens in Israel to be prepared for an emergency and to prepare to leave the country. Any Chinese traveling in Iran are also being told to depart immediately.

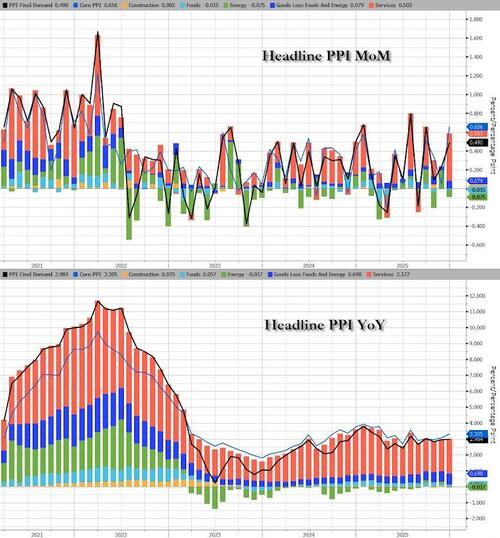

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 08:50Surging Services Costs Spark Unexpected Surge In US Producer Prices In January

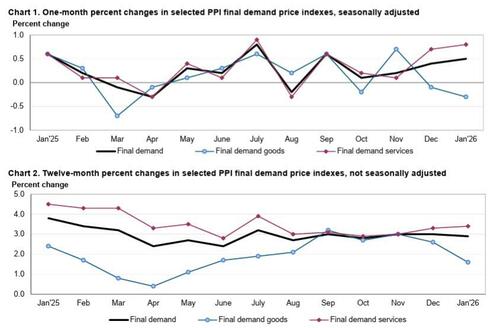

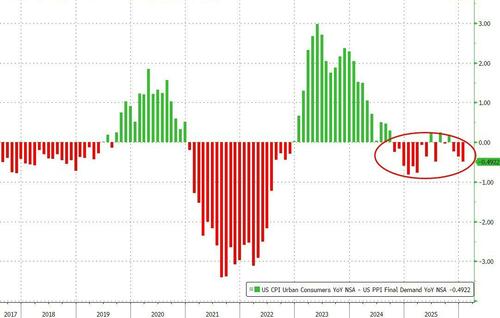

US Producer Prices came in hotter than expected in January, with the headline PPI rising 0.5% MoM (vs +0.3% exp), higher than the revised +0.4% MoM in December. This left Producer Prices up 2.9% YoY (hotter than expected but below December's +3.0%)...

Source: Bloomberg

Under the hood, we see a surge in Services costs (not tariff related) dominated the rise in PPI (while Energy saw deflation)

Final demand services: The index for final demand services advanced 0.8% in January, the largest increase since moving up 0.9% in July 2025. Most of the January rise in prices for final demand services can be traced to margins for final demand trade services, which jumped 2.5 percent. (Trade indexes measure changes in margins received by wholesalers and retailers.) Prices for final demand transportation and warehousing services advanced 1.0 percent, while the index for final demand services less trade, transportation, and warehousing was unchanged.

- Product detail: Over 20% of the January increase in prices for final demand services is attributable to a 14.4% jump in margins for professional and commercial equipment wholesaling. The indexes for apparel, footwear, and accessories retailing; chemicals and allied products wholesaling; bundled wired telecommunications access services; health, beauty, and optical goods retailing; and food and alcohol retailing also moved higher. Conversely, prices for system software publishing fell 12.2 percent. The indexes for guestroom rental and for apparel wholesaling also decreased.

Final demand goods: Prices for final demand goods moved down 0.3% in January, the largest decrease since falling 0.7% in March 2025. Leading the January decline, the index for final demand energy dropped 2.7 percent. Prices for final demand foods decreased 1.5 percent. In contrast, the index for final demand goods less foods and energy advanced 0.7 percent.

- Product detail: Nearly 80 percent of the January decline in prices for final demand goods can be traced to the index for gasoline, which fell 5.5 percent. Prices for chicken eggs, electric power, gas fuels, fresh fruits and melons, and ethanol also moved lower. Conversely, the index for search, detection, navigation, and guidance systems jumped 15.5 percent. Prices for nonferrous metals and for pork also rose.

The Energy component of PPI could be about to re-accelerate...

Core PPI (ex food and energy) surged 0.8% MoM and is up 3.6% YoY (both hotter than expected) - the fast pace of price increase since March 2025...

Source: Bloomberg

Margin pressures remain as input prices rise faster than output prices...

The bottom line is that this will likely lead to a hotter than expected Core PCE print - something The Fed watches closely.

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 08:42Futures Slide As Renewed AI Disruption And Private Credit Fears Spark Selling

The rollercoaster continues: US equity futures are in the red again, trading near session lows, and set to extend Thursday's losses with as stocks underperform after yesterday's spectacular plunge in the momentum trade as NVDA's post record-breaking earnings/guidance plunge spooked markets that nothing is resolved about where AI goes next. As of 8:00am ET, S&P futures were down 0.6%, and set for a monthly loss after a whirlwind February marked by twin fears of a bubble in the AI trade and of the technology’s disruptive power. Nasdaq futures dropped 0.7%. In the latest AI contradiction, CoreWeave plunged 12% after data center operator reported a bigger-than-expected loss and higher capex fueling concern about overspending on infrastructure. But in a mirror image, Dell is 12% higher after its outlook for sales of AI servers exceeded estimates, a sign of robust demand for machines helping fuel the AI data center build-out. 10-year Treasury yields slid below 4%, while the USD is flat. Commodities are mixed, with Energy higher and Metals mixed (Silver outperforming vs Gold flat). Today's macro data focus is on PPI and Construction Spending.

In premarket trading Mag 7 stocks are mixed: Nvidia is up 0.4% after sliding Thursday, other names are mostly lower (Alphabet little changed, Tesla -0.2%, Amazon -0.5%, Apple -0.5%, Meta Platforms -0.5%, Microsoft -0.8%).

- Block (XYZ) rallies 18% after the financial technology company said it was reducing its workforce by nearly half in a bet on AI. Jack Dorsey’s firm also raised its full-year outlook for gross profit, which was already above the average analyst estimate.

- CoreWeave (CRWV) slides 12% after the AI infrastructure software company reported a bigger-than-expected loss and boosted capital expenditures, spurring concerns about the company overspending on infrastructure.

- Flutter (FLUT) is down 15% after the gambling company reported fourth-quarter results that fell short of Wall Street estimates. Guidance for 2026 was worse than expected, according to analysts, who pointed to increasing competitive pressures in the US sports-betting market as a key concern.

- NCR Atleos (NATL) jumps 16% as The Brink’s Company said it will acquire the company in a cash and stock deal valued at about $6.6 billion.

- Netflix (NFLX) is up 8% after the streaming giant dropped out of the fight to buy Warner Bros. Discovery, effectively ending the bidding war for the Hollywood studio.

- Zscaler (ZS) is down 9% after the security software company’s second-quarter results weren’t seen as strong enough to reverse recent negative sentiment toward software companies.

In other corporate news, Netflix rose more than 7% after dropping out of the bidding for Warner Bros. Dell Technologies surged 11% following a strong sales forecast for its AI servers.

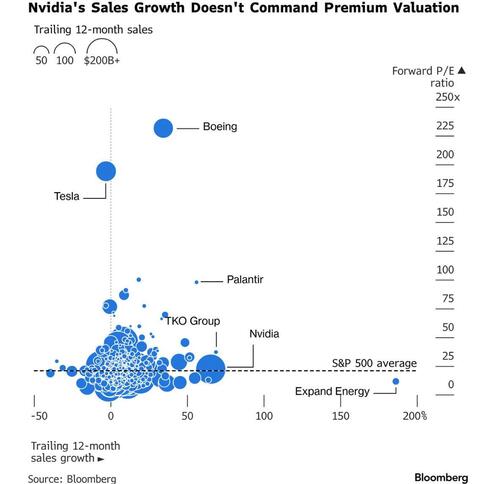

Nvidia suffered its worst day since April on Thursday, with the price action suggesting the world’s most valuable company is no longer being rewarded for spectacular results and remarkable guidance.

NVDA's plunge happens as the disruptive potential of AI has rattled US equities for weeks in what traders have dubbed the “AI scare trade.” The technology’s bellwethers have also lost momentum after powering S&P 500 gains for years, prompting investors to rotate into markets abroad and companies tied to broader economic growth.

“The outperformance highlights the possibility of a lingering overvaluation in some asset classes in the US, as well as doubts about the independence of the Federal Reserve’s future monetary policy,” said Guillermo Hernandez Sampere, head of trading at asset manager MPPM. “Barring an economic downturn in Europe, the outperformance should continue.”

“The outperformance highlights the possibility of a lingering overvaluation in some asset classes in the US, as well as doubts about the independence of the Federal Reserve’s future monetary policy,” said Guillermo Hernandez Sampere, head of trading at asset manager MPPM. “Barring an economic downturn in Europe, the outperformance should continue.”

As Wall Street tries to assess likely job losses at the hands of AI, Jack Dorsey’s financial technology firm Block is cutting 4,000 employees, nearly half its workforce, in a bet on AI changing the future of labor productivity. Then again, considering that Elon Musk fired 80% of Dorsey's last company before ChatGPT was even out - and it thrived - or that Block spent $68 million on a party a few months before the mass layoffs, suggests that the culprit here is bloat and terrible management, and not AI.

Block:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) February 27, 2026

1. spend $68 million on a party

2. 200 days later fire 40% of workers

3. blame AI pic.twitter.com/TdgXnIVGNM

The market’s unease about private credit persists. In an rerun of the collapse of First Brands, a spectacular new private credit blowup in London has Wall Street chasing billions. And a private credit fund overseen by Apollo Global Management cut its dividend and marked down the value of its assets amid signs of strain in parts of its loan book.

Elsewhere, Anthropic, the AI start-up that has wiped billions off the market value of US stocks, remains in focus. US lawmakers, flummoxed by the Pentagon’s negotiating tactics, are warning that carrying out those threats would have significant consequences for the military ecosystem. Meanwhile, investment-grade bond markets, which had emerged as a safe haven during recent AI-driven swings in equities, are starting to show signs of strain.

US stocks saw inflows of $2.2 billion in the week ended Feb. 25, according to BofA citing EPFR Global data. Strategists led by Michael Hartnett see international stocks outperforming US for the rest of this decade.

"I don’t see any major correction coming, but any hint of a recession linked to AI in the US would certainly trigger some unpleasant trading,” said Andrea Tueni, head of sales trading at Saxo Banque France. “Europe is currently better positioned than the US and outperforming as its tech sector is much smaller and there is much less uncertainty on monetary policy.”

Earnings season wraps up next week, and has so far been somewhat disappointing, with the fewest S&P 500 companies beating estimates since 2022. Of the 481 to have reported so far, 73.4% have beaten forecasts, while nearly 22% have missed. No major US companies are expected to report on Friday, but Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report is due on Saturday, including Greg Abel’s first annual letter to shareholders on performance since taking over as CEO from Warren Buffett.

Europe’s Stoxx 600 was on track for an eighth straight monthly advance, its longest such streak in more than a decade; telecommunications and mining stocks lead gains, while travel and consumer products shares edged lower. Here are the biggest movers Friday:

- Deutsche Telekom shares rally while Vodafone dips following an El Español report that Telefonica is in talks over a potential acquisition of 1&1 in Germany

- Prysmian shares reverse earlier losses to trade as much as 2.3% higher following 4Q results from the Italian cable make

- Holcim gains as much as 1.5% after the French building materials firm reported fourth-quarter earnings that were slightly ahead of expectations and an outlook that is unlikely to trigger any major revisions to estimates, according to analysts

- Clariane shares jump 17%, the most since June, as analysts highlight improving margins and cost-saving initiatives at the French nursing home operator

- Saint-Gobain shares fall as much as 3.2%, the most since Jan. 13, after the French construction materials producer reported fourth-quarter results. Jefferies noted that like-for-like sales in the period trailed expectations

- Melrose Industries plunges as much as 16%, the biggest drop in almost a year, after earnings guidance from the aerospace business fell short of expectations, overshadowing a profit and cashflow beat delivered in 2025

- BASF shares fall as much as 5.4%, after the German chemicals company’s full-year results disappointed analysts, who expect consensus downgrades, even though a January pre-release had already revealed price and currency woes at the company

- Grifols shares declined as much as 8.3%, the most since April, after the Spanish company’s adjusted Ebitda for the fourth quarter missed estimates and it issued guidance that analysts say fell short of expectations

- Valeo falls as much as 4.9% following its results, despite guidance implying upgrades to consensus free cash expectations, after this metric also surprised to the upside in the second half of the year. Net income was, however, impacted by higher tax

- Wizz Air shares slid as much as 10%, the most since July, after shareholder Indigo Partners offered 10 million shares priced at £12.50, a discount of 6.4% to Thursday’s closing price

- Fugro shares fall as much as 12%, the most since September, after the Dutch geological data company saw its year-over-year adjusted Ebit plunge by 92% in what Jefferies says was a “challenging winter season”

Asian stocks traded mixed, with a key regional benchmark on track to close its best February on record as investors snapped up shares of the region’s AI infrastructure companies. The MSCI Asia Pacific Index gain as much as 0.6% Friday. South Korea’s Kospi fell 1%, as chipmakers Samsung and SK Hynix fell. Key gauges rose in Japan and Hong Kong, while Taiwan’s market was closed for a holiday. Asian stocks have been outperforming global peers, with the region’s hardware firms seen as beneficiaries of the AI buildout even as concerns grow over spending levels and business disruption. The MSCI regional gauge is up 6.7% this month, poised for the best February since it started trading in 1998. Chinese technology stocks in Hong Kong capped their worst month in two years, weighed by weak earnings and a lack of buying by mainland investors. Sentiment toward China’s Internet giants has cooled amid concerns over valuations and rising competition that’s eroding corporate bottom line. Meanwhile, global investors offloaded nearly $5 billion of South Korean equities on Friday, in a sign of profit taking after the equity benchmark rallied nearly 50% this year. The index rose past the 6,000 threshold this week, just a month after surpassing President Lee Jae Myung’s political goal of 5,000.

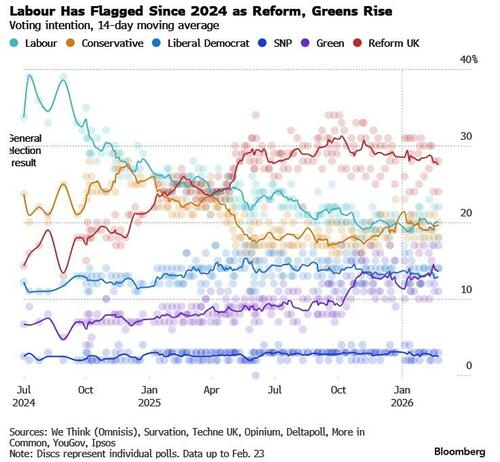

In FX, the dollar was set for a fourth straight monthly loss. The Norwegian Krone led G10 currencies with a +0.54% rise. The pound fell slightly against the dollar after a special election in the UK laid bare the unpopularity of Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s government.

In rates, treasuries extended gains, with the 10-year note on track for its best month in a year after yields have tumbled 26 basis points in February to 3.98%. Outperformance by front-end and belly steepened 2s10s spread by about 1bp, 5s30s by about 1.5bp. 10-year gilts and bunds are slightly cheaper vs US benchmark

In commodities, oil rose again, after sliding on Thursday. Gold traded flat, with prices headed for a seventh consecutive monthly advance.

The cross-asset moves reflect sustained demand for havens amid policy uncertainty from the Trump administration, tensions in the Middle East and questions about the strength of US economic growth. Swap traders added to bets on Federal Reserve interest-rate cuts, with a July move again almost fully priced after being briefly scaled back earlier this week.

US economic data slate includes January PPI (8:30am), February MNI Chicago PMI (9:45am, several minutes earlier for subscribers), December construction spending (10am) and February Kansas City Fed services activity (11am). No Fed speakers are scheduled. Bloomberg Economics expects producer price inflation, which shows price trends before they reach consumers and feeds into the Fed’s preferred gauge of inflation, the personal consumption expenditures index, to have slowed to 0.2% in January from 0.5%. Potentially, that could bolster the case for further rate cuts.

Market Snapshot

- S&P 500 mini -0.3%

- Nasdaq 100 mini -0.3%

- Russell 2000 mini -0.8%

- Stoxx Europe 600 +0.2%

- DAX +0.2%

- CAC 40 -0.1%

- 10-year Treasury yield -1 basis point at 3.99%

- VIX +1.1 points at 19.74

- Bloomberg Dollar Index little changed at 1188.36

- euro little changed at $1.1801

- WTI crude +1.8% at $66.38/barrel

Top Overnight News

- The United States and Iran made progress in talks over Tehran's nuclear program on Thursday, mediator Oman said, but hours of negotiation ended with no sign of a breakthrough that could avert potential U.S. strikes amid a massive military buildup. RTRS

- Vice President JD Vance said Thursday that while military strikes against Iran remain under consideration by President Donald Trump, there is “no chance” that such strikes would result in the United States becoming involved in a years-long, drawn-out war. WSJ

- Anthropic rejected the Pentagon proposal to settle a dispute over terms for military use of its AI software. BBG

- A long-running conflict between Pakistan and Afghanistan’s Taliban regime has turned into what Pakistan declared Friday to be “open war,” with attacks reported in Kabul and along the neighbors’ shared border. WSJ

- China announced it would remove a reserve requirement for forward contracts selling the yuan in a move aimed at cooling the currency’s advance. The yuan snapped its longest winning streak since 2010. Still, options traders are betting on a stronger yuan. FT, BBG

- Inflation in Japan’s capital cooled below the central bank’s 2% target for the first time in over a year, but the slowdown is unlikely to derail further interest rate hikes. WSJ

- Mizuho Financial Group Inc. is planning to replace about 5,000 administrative jobs in Japan with artificial intelligence over the next 10 years, as the country’s third-largest lender tries to boost productivity. BBG

- The pound fell to its lowest level against the euro in more than two months as the Greens won a by-election in Manchester and Reform UK received the second-highest number of votes. The result underscored the threats facing PM Keir Starmer. BBG

- Netflix shares jumped premarket (NFLX +740bps premkt) after it dropped its bid for Warner Bros., clearing the way for Paramount’s $111 billion deal. The decision allows the streamer to focus on buybacks and its “build vs. buy” strategy. BBG

- IG bond markets are showing signs of stress, with spreads widening as investors grow wary of default risks in the software sector and pressure in private credit. Risk premiums, however, remain below long-term averages. BBG

Trade/Tariffs

- China's MOFCOM announces adjustments to anti-discrimination measures against Canada effective Mar 1st till Dec 31st 2026, will not impose relevant tariffs on some imports from China.

- Japan's PM Takaichi said US needs to honour its commitments on tariffs.

A more detailed look at global markets courtesy of Newsquawk

APAC stocks were ultimately higher heading into month-end but with price action choppy following the weak handover from the US, where sentiment was clouded by tech weakness, while participants also digested the recent US-Iran talks in Geneva. ASX 200 mildly gained as strength in tech and telecoms atoned for the losses in financials and consumer stocks. Nikkei 225 traded indecisively amid a firmer currency and a slew of mixed data releases from Japan, in which Industrial Production disappointed, Retail Sales topped forecasts, and Tokyo CPI printed firmer-than-expected but slowed across the board with the Core reading falling beneath the central bank's 2% price target for the first time since October 2024. Hang Seng and Shanghai Comp were varied with outperformance in Hong Kong as participants digested earnings releases from the likes of Baidu and Sun Hung Kai Properties, while the mainland initially lacked direction in the absence of fresh catalysts and ahead of next week's annual "two sessions", while Trump-Xi summit preparations were said to falter. However, late upside was seen after comments from China's Politburo meeting in which it stated that China's development process during the 14th Five-Year Plan is extraordinary and that it is necessary to continue to implement a more active fiscal policy and a moderately loose monetary policy.Top Asian News

Top Asian News

- China Politburo held a meeting on Friday and noted that China's development process during the 14th Five-Year Plan is extremely unusual and extraordinary. Said that it is necessary to continue to implement a more active fiscal policy and a moderately loose monetary policy. Necessary to focus on building a strong domestic market and step up the cultivation and expansion of new growth momentum.

European bourses (STOXX 600 +0.3%) are broadly firmer, with the SMI (+0.7%) the clear outperformer after Swiss Re (+3.6%) posted a 47% Y/Y rise in 2025 net profit while announcing a USD 500mln share buyback. Lagging behind its peers is the CAC 40 (-0.1%), with very company-specific news to drive the index. European sectors are mixed. Telecommunications (+1.3%) outperform after Spain's Cellnex (+0.6%) saw 2025 operating profit rise more than double annually and Telefonica (+3.7%) reportedly negotiating the purchase of 1&1 (+9.4%)in Germany in a EUR 5bln deal. On the flip side, Travel and Leisure (-1.8%) is underperforming despite positive IAG (-5.5%) earnings, in which the Co. beat FY profit expectations and announced a EUR 1.5bln share buyback.

Top European News

- UK former Deputy PM Rayner noted the Gorton and Denton by-election results are a "wake up call" and Labour "has to be braver"; Sky News suggests these remarks will be taken as a direct aim at UK PM Starmer and his leadership.

- EU Commission eyes a legal loophole to bypass Hungary's veto of a EUR 90bln euro loan, according to FT.

- UK Green Party wins parliamentary seat in Gorton and Denton, defeating UK PM Starmer's Labour in the by-election.

FX

- DXY is choppy but ultimately slightly softer following subdued APAC trade amid mixed sentiment, whilst the tone in Europe is tentative. Modest downticks in the index were seen as the EUR strengthened following the hotter-than-expected French CPI data (more below). Aside from that, newsflow in the European morning has been on the quieter side as USD traders gear up for US PPI data later in the session. DXY resides in a current 97.611-97.824 range at the time of writing, within Thursday’s 97.489-97.984 parameter.

- EUR/USD eked mild gains after oscillating around the 1.1800 focal point overnight, with a more convincing move above the level seen after the hotter-than-expected French and Spanish Prelim CPI metrics. EUR/USD resides in a 1.1789-1.1822 range awaiting the German Prelim CPI later today. The single currency then slipped to the unchanged mark after German state CPI metrics, where the Y/Y metrics generally showed a bit more cooling than what is forecasted for the mainland.

- GBP/USD languished near the 1.3500 level following the prior day's underperformance owing to credit concerns, and with overnight price action contained after UK GfK consumer confidence fell to its lowest level that was last seen in November. Overnight, UK journalists focused on the Gorton and Denton by-elections in which the Green party won, with Reform second and Labour third. With Labour losing a seat they held for almost 100 years, UK PM Starmer's leadership could be at risk. Nonetheless, GBP/USD saw little reaction to the results announcement, and currently resides in a 1.3461-1.3507 range, after finding support at its 200 DMA (1.3442) yesterday. Ahead, BoE’s Chief Economist Pill is due to give some remarks.

- USD/JPY retreated amid the early subdued risk appetite and following a slew of data, including Tokyo CPI, which printed firmer-than-expected across the board, but slowed from the previous with Core inflation back beneath the BoJ's price goal. The pair pared back some losses as the DXY recouped some overnight losses. USD/JPY trades in a 155.54-156.12 range vs yesterday’s 155.70-156.43 parameter.

- Antipodeans rebounded from the prior day's trough and narrowly outperform in the European morning, but with further upside contained by the mixed risk appetite and amid a weaker CNH, which was pressured after the PBoC actions to slow currency appreciation, in which it cut the FX risk reserve ratio to 0% and set a weaker-than-expected CNY fix by maintaining it at the prior day's level.

Fixed Income

- USTs are firmer by a handful of ticks this morning, and trades within a 113-16 to 113-19 range. Really not much driving things for the US paper this morning, and remains towards the prior day’s peaks. The upside in USTs on Thursday was facilitated by subdued risk appetite and a decent 7yr auction. Focus remains on the geopolitical situation, following US-Iran talks. Meetings have concluded, and whilst there have reportedly been some positive developments, uncertainty remains. Reports suggest that US President Trump is expected to convene senior advisers on Friday for detailed discussions on Iran and to decide on a course of action toward Tehran. Internal deliberations are said to be focused not on whether a strike would occur but on its scope and potential targets. Next up, US PPI.

- Bunds are incrementally firmer/flat, and currently reside within a 129.76 to 129.99 range. Initially held towards recent highs, but has since slipped towards the unchanged mark following the hotter-than-expected French/Spanish inflation metrics. Though the German State CPIs thereafter spurred some modest upticks in Bunds, given the Y/Y metrics generally showed a bit more cooling than what is forecasted for the mainland.

- Gilts are firmer by around 10 ticks, to currently trade near the upper end of a 93.00-93.30 range. Overnight, UK journalists focused on the Gorton and Denton by-elections in which the Green party won, with Reform second and Labour third. With Labour losing a seat they held for almost 100 years, UK PM Starmer's leadership could be at risk – which in theory would place pressure on UK-assets. This has not been reflected in price action this morning, though analysts at GS opined that the risk had already been priced in by markets.

- Japan sold JPY 2.15tln in 2-year JGBs; b/c 3.32x (prev. 3.88x); average yield 1.244% (prev. 1.253%).

- Australia sold AUD 800mln 2.75% November 2028 bonds, b/c 3.86, avg. yield 4.1849%.

Commodities

- WTI Apr’26 and Brent May’26 futures are firmer within USD 64.85-65.90/bbl and USD 70.42-71.49/bbl intraday ranges thus far, respectively. Gains follow yesterday’s US-Iran negotiations, which ultimately failed to reach an accord, but the sides agreed to continue technical talks. Mediators reported "unprecedented openness to new and creative ideas". Both sides reportedly moved closer on specific elements of an agreement related to nuclear limits and sanctions relief. That being said, major sticking points remain.

- Spot gold trades within a narrow range after only modestly gaining on yesterday’s US-Iran saga, which ended in no deal, but talks are poised to continue next week. Traders will be focused on any potential US military action this weekend in a bid to pressure Iran. Spot gold resides tight USD 5,167-5,200.64/oz range at the time of writing. Spot silver is firmer by some 1.5% intraday but contained to within Wednesday’s ranges.

- Base metals are firmer across the board despite the choppy risk tone in Asia, but prices are underpinned by the softer USD. Some desks attribute the rise to the stalled US-Iran talks and strengthening demand signals from China. The upside also comes ahead of next week’s China “Two Sessions”, where formal approval of the 15th Five-Year Plan and new stimulus measures for infrastructure and technology (AI, EVs, grid networks) are anticipated. 3M LME copper resides in a USD 13,243.73-13,508.13/t.

- London Metal Exchange announces the consultation for introducing regulatory position limits, exemptions and position management controls.

- Iron ore port stockpiles hit record levels in China as mines continue to add supply.

- Abu Dhabi reportedly offers more oil to partners, heading into the OPEC+ meeting, Bloomberg sources say.

- India is reportedly looking to cut coal imports for power plants at least 30% this year, sources say.

- China SHFE warehouses weekly changes: Copper +43.7%, Aluminium +19.7%, Zinc +44.9%.

- A local ceasefire has been established near the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, TASS reported. Further by RIA stating one power line is being repaired at the power plant.

Geopolitics: Middle East

- US authorises the departure of some embassy personnel and families from Israel amid safety risks.

- Iran urges US to abandon "excessive demands" to reach deal, Sky News Arabia reported citing AFP.

- Iranian spokesperson said "In the event of any conflict, American soldiers and their equipment will be destroyed, and all US resources and interests in the region will be within the range of Iranian forces", via Iran International.

- Top Middle East commander briefed US President Trump on military options on Iran, according to ABC News.

- US VP Vance said negotiations depend on what the Iranians do and there is no chance that any potential strikes on Iran will result in engaging in a war for years.

- US President Trump is expected to convene senior advisers on Friday for detailed discussions on Iran and to decide on a course of action toward Tehran, according to Israel Hayom citing US officials. Internal deliberations are said to be focused not on whether a strike would occur but on its scope and potential targets, while options under discussion include nuclear facilities, missile sites, state institutions and infrastructure.

- Iranian Foreign Minister said further progress has been made in our diplomatic engagement with the US, also said mission of the technical teams is as important as our mission.

- Oman's Foreign Minister is scheduled to meet with US VP Vance and other US officials in Washington on Friday.

Geopolitics: Others

- China said it is not possible to join denuclearisation talks at this stage.

- AFP reported of clashes near a major border crossing between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

- Afghan Ministry of Defence said their military operation resulted in casualties among Pakistani forces and came in defence of their territory and people, while it vowed to respond to future attacks.

- Loud explosion heard in Afghanistan's capital of Kabul and Pakistani fighter jets are reportedly conducting a raid on Kabul.

US Event Calendar

DB's Jim Reid concludes the overnight wrap

d

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 08:30"Torn The Roof Off" British Politics: Starmer Stunned After Green Party Steals Labour Seat

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer is under pressure to reinvent his ailing Labour government with a leftwards pivot after the Green Party captured one of its House of Commons seats via a special election.

The result underscores the recent fragmentation of UK politics and the disruption of long-held electoral certainties.

It has “torn the roof off” British politics, said Green Party Leader Zack Polanski.

Spencer’s win marks the first-ever by-election victory for the Greens, as well as their first seat in northern England, highlighting the increasing reach of the left-wing party in a context where Labour voters are abandoning it in both directions.

Spencer’s margin of victory was much more comfortable than commentators had expected, with polls consistently understating the Greens’ appeal.

The swing from Labour was 26% in Gorton and Denton, and the Greens now have five MPs in Parliament.

Andrea Egan, general secretary at workers’ union Unison, said Labour should be “taking the fight” to Reform UK Leader Nigel Farage “rather than letting him set the agenda.”

As Tom Jones reports below for TheCritic.co.uk, the election has grim implications.

The Gorton and Denton by-election, by virtue of having been won by the Greens, marks a more momentous shift for the left than the right. Ava Santina has written about this for us, and a recent Critic Show episode is devoted entirely to the fracturing of the left.

But like the overweight kid trying to avoid getting near the ball in PE, just because you don’t win, that doesn’t mean there aren’t lessons to be learned.

The first is that Reform may need to start thinking about expectation management. As an insurgent party, they were happy to talk up their chances of winning in order to build the narrative that the two main parties are finished. But this made the race seem closer than the result ended up being: 4,000 votes behind the Greens and just over 1,000 votes ahead of Labour therefore will be made to seem like an underperformance by the media.

It was not. In terms of the size of the swing needed from the 2024 General Election, Gorton and Denton was 413th on Reform’s target list. Even with their polling shoring up at around 30 per cent, as it is in national polls, turning the sixth Labour seat over was a stretch too far. On the upside, a national campaign against the Greens will be a much more favourable proposition for Reform, coming as it does against a weaker campaigning machine than Labour — and increased scrutiny on the Green Party, which it will fail.

A lesson may also be on the need to find local candidates. I hate that local candidates boost election performances, I hate that Hannah Spencer claimed she had never seen Matt Goodwin in the local Asda “doing his big shop”, but most of all I hate that it works. A local candidate would not have swung Gorton and Denton their way, but there will be a significant number of seats where it will. It’s yet another problem for Reform’s candidate selection team to deal with.

As for the other right-wing parties, the question is, “why bother?”

The Conservatives took just 706 votes. 1.9 per cent of the vote. That is their lowest ever vote share in a by-election. They lose their deposit for the first time at an English by election for nearly 40 years.

We have heard much about the need for a Reform-Conservative pact. It has come, overwhelmingly, from establishment media figures whose professional relevance depends on preserving their access to the Conservative Party — and who can see that access, and therefore their own influence, draining away. Such a pact would necessitate the Conservatives to stand aside in hundreds of seats like this. It is so ingrained in the Conservative psyche to stand candidates everywhere that it is part of the party’s constitution. Farage has been burned before with a Conservative pact — it is incumbent on the Conservatives to make any such a deal happen.

The Conservative statement after the result spoke much about this result rendering Starmer a lame duck, but nothing about their failure to play any role in this result being delivered.

Meanwhile Advance UK, the Ben Habib vehicle, took 154 votes — less than the Monster Raving Loony Party. A vision of Restore Britain’s future? Perhaps. There is a question here. If things are really as bad as the leaders of these parties claim, then how can they justify siphoning off votes from adjacent right-wing parties over ever-finer points of right-wing doctrine? When the house is on fire, it is a strange moment to insist on arguing about the exact brand of extinguisher.

Perhaps parties formed with the sole aim of giving histrionic social media addicts something to do will not be Britain’s salvation. Who knew.

Finally, the lesson that all parties of the right should take is in the dangers of sectarian voting.

For a long time the conventional parties have been happy with sectarian voting, so long as it delivered conventional parties.

The salience of the Muslim vote in this election — coupled with the Green Party’s campaign videos in Urdu and Bangla — has reinforced a narrative that has been gathering force since the rise of the so-called “Gaza independents”: that Britain has a sectarian voting problem that can no longer be ignored.

It is fast becoming an ingrained part of our political culture: Sky’s coverage of the result included Sam Coates examining and speaking about the proportion of the seat that is ethnic minority.

There is a risk here.

A political class steeped in American news and habits of thought may interpret this development as merely the British version of familiar US-style demographic politics, where politics is more attuned to minute changes amongst identity and interest groups.

It is not. American immigrants, and therefore their voting patterns, are markedly different to those in Britain. We are not getting “suburban moms”.

The Electoral Commission grants Democracy Volunteers access to polling stations during elections, and the group has reported seeing “concerningly high levels” of family voting (an illegal practice in which two voters occupy a single polling booth, often with one directing the other’s vote) in the by-election.

John Ault, director of Democracy Volunteers, said: “Today we have seen concerningly high levels of family voting in Gorton and Denton. Based on our assessment of today’s observations, we have seen the highest levels of family voting at any election in our 10 year history of observing elections in the UK.”

He added: “We rarely issue a report on the night of an election, but the data we have collected today on family voting, when compared to other recent by-elections, is extremely high. In the other recent Westminster parliamentary by-election in Runcorn and Helsby we saw family voting in 12 per cent of polling stations, affecting 1 per cent of voters. In Gorton and Denton, we observed family voting in 68 per cent of polling stations, affecting 12 per cent of those voters observed.”

Manchester City Council have hit back, arguing that “No such issues have been reported today”, and blaming Democracy Volunteers for not reporting these issues at the time. This issue is too obvious to ignore (although some will try), and at least some parties will find it politically expedient to oppose it. These voting patterns have been documented for a long time. Perhaps, after the next election, we will finally have the chance to deal with them. Small mercies, but mercies nonetheless.

Angela Rayner, the former deputy prime minister who is bookmakers’ favorite to succeed Starmer, said the result was “a wake-up call.”

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 08:25New Kansas Law Ends Transgender Activist Madness

It's a disturbing commentary on our times when the concept of men and women being required by law to admit their proper biological sex becomes headline news, but here we are.

For the past decade, transgender ideology (with zero basis in scientific reality) has surged to the forefront of our cultural zeitgeist. Never before in the history of the western world has one tiny minority of people received so much privilege and protection from governments and the corporate establishment. Furthermore, this small group of mentally ill people has triggered a political firestorm that is changing the face of the US.

Why did the Democratic Party and so many wealthy and powerful elites choose transgenderism as the hill to die on? Why do they lie and claim there are no differences between men and women? Why do they want to give unhinged men access to women's bathrooms and locker rooms? Why are they so intent on indoctrinating children with gender fluid propaganda? Why do they want to let little kids mutilate their bodies with sex hormones and surgeries? It's hard to say.

One's first inclination is to assume that these people are evil. How else can we explain their behavior? The other consideration is that they are all suffering from mental instability. At bottom, there is no place for transgender ideology in a civilized society, and it would appear that the Kansas GOP has come to the same conclusion.

Kansas has recently enacted a law that restricts transgender individuals from using bathrooms, locker rooms, and similar multi-occupancy facilities in government-owned or leased public buildings (such as schools, universities, and state facilities) that do not align with their sex assigned at birth. The legislation, known as House Substitute for Senate Bill 244 (SB 244), requires people to use single-sex facilities based on their biological sex at birth.

The new law also requires trans activists to use their real biological sex assigned at birth on their driver's licenses, birth certificates and other official documents. In other words, the LARP is over, at least in Kansas.

Violators could face civil lawsuits, with a minimum of $1,000 in damages for each instance where someone believes they shared a facility with a transgender person (often described as a "bounty-style" provision). Repeated violations can lead to criminal penalties

Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly vetoed the measure but the Legislature’s GOP supermajority overrode it last week. Republican state lawmakers across the U.S. have pursued a series of measures to prevent a repeat of the Biden era, which resulted in a dizzying avalanche of trans related special protections and privileges, essentially making transgender activists into an elite class of citizen.

Western allies like Canada, Australia and parts of Europe have gone even further, making it a criminal offense to criticize trans concepts or trans activists online. The US is the only country so far to reverse course.

Not surprisingly, the number of people affected by the law is minimal. Only 1700-1800 individuals will end up having to change the drivers license or birth certificate. Consider for a moment, though, that an entire state was being held hostage by only 1800 people. Why would any society adapt so many standards and practices for a such meaningless percentage of the population?

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 07:45Restoring Britain

Authored by Laura Hollis via The Epoch Times,

There’s a revolution brewing across the Big Pond.

The British people were already fed up with the Labour government headed by Prime Minister Keir Starmer. And then the man Starmer appointed to be ambassador to the United States—Peter Mandelson—was exposed as having a deep friendship with sex predator Jeffrey Epstein, even after Epstein was convicted on charges of sex with a minor in 2008. Mandelson is now under investigation for possibly passing sensitive government information to Epstein. Starmer is viewed as being crippled by these revelations and losing support within his own party.

But it’s the split on the political Right that is most interesting at the moment. For quite some time, Nigel Farage’s Reform UK Party has been the favorite to unseat Labour in the next general parliamentary election in 2029. Farage came into the international spotlight as the leader of the movement to take Britain out of the European Union (“Brexit”). But Farage is increasingly viewed as having become “establishment,” particularly on the question of what to do about the millions of Muslim migrants who have poured into England and the rest of the United Kingdom.

Farage and former fellow Reform UK MP Rupert Lowe had a serious falling-out last year.

Lowe was—and is—pushing for mass deportations, a policy that Farage has dismissed as “beyond the point of reasonableness, of decency, of morality.”

Lowe publicly criticized Farage’s leadership of Reform UK; Farage responded by kicking Lowe out of the party, accusing him of “bullying” staff members and of making threats against party chairman Zia Yusef. It would further appear that Farage was responsible for a police raid on Lowe’s home to confiscate his firearms. (No charges were filed against Lowe, and his guns were returned to him.)

Lowe has returned with a vengeance. Two weeks ago, he announced the formation of a new political party, “Restore Britain.”

“Restore,” as it is now commonly referred to, makes nearly daily policy pronouncements on social media platform X.

Among the policies Lowe says the party will advocate for are banning the burqa, return of the death penalty for the most heinous crimes, stronger self-defense protections for British homeowners, reversal of convictions for those accused of “hate speech crimes” and commutation of their sentences, laws ensuring freedom of speech, and mass deportations, starting with migrants who have committed crimes, including and especially the men who have participated in the “rape gangs.”

Perhaps more than any other issue, this one has galvanized the British public. People are shocked to discover that the government was too timid to arrest and prosecute men—largely Pakistani—who were known to be keeping young girls as sex slaves, fearing being called racist. Lowe has sworn he’ll bring all the facts to light and earlier this week released a victim’s statement indicating that members of local police forces were not only aware of the Pakistani rape gangs but, in some cases, were participants.

All of this has created a perfect storm of outrage, and Lowe has very clearly hit a nerve.

Restore Britain has acquired 100,000 members in less than two weeks. To put things in perspective, that places Restore Britain fifth—behind the top four political parties—by membership: Reform UK currently has 280,000 members, Labour 250,000, the Green Party 198,000 and the Conservative Party 123,000.

In his inimitable fashion, X CEO Elon Musk has weighed in, expressing support for Restore Britain.

Their X account now has over 300,000 followers, and videos posted are generating millions of views. Even Americans—who cannot vote or become members of any British political party—are throwing in financial support for Lowe’s Restore party. X is filled with fan art, posters, memes and slogans backing Restore Britain and Lowe. (A favorite is “Aim High—Vote Lowe.”)

The British parliamentary system is very different from America’s political structure, and their general election is—absent some intervening event—three years away. But this feels for all the world like a MAGA-esque revolution in the making. On the Left, the dominant party is Labour—presently in power—which defends unlimited migration into the UK, insists that Muslims add to the rich tapestry of British culture, refuses to conduct an inquiry into the Pakistani rape gang investigations, and prosecutes citizens who complain about the impact of mass migration: the crime, the outrageous government expenditures, the benefits given freely to migrants (while native British struggle to find housing and wait for health care), the unprosecuted rape of thousands of white British girls, and the denigration of British society and culture.

On the Right, the Tories have traditionally dominated. But that party saw five weak prime ministers within 14 years (Rishi Sunak, Liz Truss, Boris Johnson, Theresa May, David Cameron), leaving it without much public support, and creating the possibility that Reform UK will have the greatest number of seats in the next parliament, and party leader Nigel Farage will become prime minister.

At least, that was the narrative until a couple of weeks ago. Now Restore Britain is being viewed by its supporters—much as Donald Trump was in 2015—as the dark horse that might surprise everyone in 2029.

Polls conducted this week asking Britons their voting intentions show Restore Britain—which is not even an officially approved party yet—already with 7 percent support. (Keep in mind that these numbers are divided among 10 political parties, with Reform UK having the largest percentage, at 25 percent.) Reform UK is trying to stave off defections, insisting that Restore Britain will “split the vote,” and cannot possibly get enough seats in Parliament to elect the prime minister, thus handing victory to Labour again (or, God forbid, the Green Party).

But this is exactly what establishment Republicans in the United States said when Trump entered the presidential race in 2015.

In the UK now, as in the U.S. then, citizens are disgusted with traditional political parties and their government’s inability—or refusal—to perform what is viewed as its most fundamental responsibility—protecting the British public and preserving the country.

It’s going to be fun to watch.

Tyler Durden Fri, 02/27/2026 - 07:20Memory Crunch Will Spark "Tsunami-Like Shock" On Global Smartphone Shipments

Readers have been briefed on the emerging global high-bandwidth memory (HBM) supply crunch, driven by soaring data center demand. We have tracked the progression of this theme for months through what seem to be almost weekly developments, ranging from notable institutional research desks and industry insiders to more recent warnings from electronics device companies about looming shortages and price spikes.

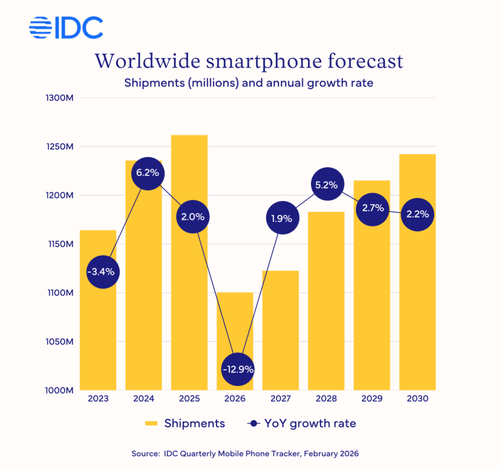

Now, market research firm International Data Corporation (IDC), which tracks handset shipments, has issued an apocalyptic warning: the smartphone market is headed for a historic downturn due to a memory crunch.

IDC estimates that global smartphone shipments will plunge 12.9% in 2026 to 1.1 billion units, the lowest annual level in over a decade. This outlook is much gloomier than IDC's November forecast.